I’ve spent some time in the past year reclaiming horror, but I’m not going to do quite that with The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Still, it’s my favorite book, and I’ve enjoyed writing about the spookiness of the green light. Today’s post is about how and why Fitzgerald plays with horror elements in this work.

Gatsby’s Mystique

- The first time Nick sees Gatsby, we get this description: “The silhouette of a moving cat wavered across the moonlight and turning my head to watch it I saw that I was not alone—fifty feet away a figure had emerged from the shadow of my neighbor’s mansion…he gave a sudden intimation that he was content to be alone—he stretched out his arms toward the dark water in a curious way, and far as I was from him I could have sworn he was trembling.”

- The questions about Gatsby’s past, particularly if he has ever killed a man.

- He appears/disappears a lot: in the opening scene, when Nick meets him for the first time, at the restaurant with Meyer, and when he goes to Nick’s to reunite with Daisy.

Gatsby’s Mansion

Gatsby’s mansion is a colossal Gothic structure. While it starts as a place of joviality, it morphs over the course of the book as Meyer’s people move in, and it becomes dark and dusty. The Luhrmann film adds Klipspringer playing the organ instead of the piano, which makes sound like to Dracula’s castle. This fits perfectly, since a lot of “thirsty” vampires show up regularly at Gatsby’s to party, and he is at once charismatic and sinister.

The Valley of Ashes

Let’s put in bold everything that’s creepy, shall we?

“This is a valley of ashes — a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.”

But above the gray land and the spasms of bleak dust which drift endlessly over it, you perceive, after a moment, the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg. The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic — their irises are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a nonexistent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away. But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.“

Ghosts

The words “ghost” or “ghostly” appear 10 times, “phantom” once, and “ectoplasm” once. There are 50 references to white and 14 to pale. There are 8 vanishes, 8 groans, and 4 hauntings. In the opening scene at Daisy’s house, the curtains are not described as ghostly, but Fitzgerald writes, “I must have stood for a few moments listening to the whip and snap of the curtains and the groan of a picture on the wall,” which has a faintly ominous sound (and certainly would look like ghosts). George Wilson is described multiple times as a ghost. First, relation to his wife Myrtle who “walks through him,” and then, in his appearance—pale and dusty. He almost morphs into a zombie-like person at the end, shambling, moaning, and out to kill.

Sociopaths

Let’s compare all of the sociopaths in The Great Gatsby according to these 6 descriptors from Psychology Today.

- Disregard laws, social mores, & others’ rights

- Fail to feel remorse or guilt

- Display violence, nervousness, and/or agitation

- Can’t hold steady job or stay in one place for long

- Struggle to form attachments

- Commit haphazard, spontaneous crimes

Creepy 20’s Music

- “The Sheik of Araby”, which goes, “I’m the Sheik of Araby. Your love belongs to me. At night when you’re are asleep into your tent I’ll creep ——”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofXvX5wtyY8

- “Ain’t We Got Fun?” is a bitter song about wealth disparity. Klipspringer plays it for Gatsby, Daisy, and Nick as they sit gloomily in the dark.

Voyeurism and Rape Culture

As an observing narrator, Nick comes off like a bit of a voyeur, but then he says these things, and it gets threatening:

“I liked to walk up Fifth Avenue and pick out romantic women from the crowd and imagine that in a few minutes I was going to enter into their lives, and no one would ever know or disapprove. Sometimes, in my mind, I followed them to their apartments on the corners of hidden streets, and they turned and smiled back at me before they faded through a door into warm darkness. At the enchanted metropolitan twilight I felt a haunting loneliness sometimes, and felt it in others…”

And then this one about Jordan:

“Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan, I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs, and so I drew up the girl beside me, tightening my arms. Her wan, scornful mouth smiled, and so I drew her up again closer, this time to my face.”

Gatsby also engages in sexual dominance. About his early encounters with Daisy, it says, “He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously — eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand.” In the current storyline, he works to get her to say what he wants her to say and do what he wants her to do.

Wilson tells his neighbor, “I’ve got my wife locked in up there,” without explaining the affair, so it sounds terrifying.

Then there’s Tom.

The Death Drum

There are multiple references to death. In the larger sense, the post-war setting encompasses the trauma of massive death. On the way to the city with Nick for the first time, Gatsby talks about the “piles of dead.” As they cross into the city (and elsewhere in the text), Nick reflects on how America has changed since its discovery, which may be a reference to the deaths of the American Indians, since the link between war and imperialism are so close. Then, “A dead man passed [them] in a hearse heaped with blooms,” connecting the individual death with the massive, lest it be forgotten why death matters. When they arrive at the speakeasy for lunch with Meyer Wolfsheim, Meyer discusses all his friends who have died, especially Rosy Rosenthal, who was shot in an establishment across the street. This is, of course, right before Nick notices Meyer’s super awesome human molar cuff buttons, an image of conquest that smacks of war.

Later on in the novel, there’s the horrific description of Myrtle’s death:

“…its driver hurried back to where Myrtle Wilson, her life violently extinguished, knelt in the road and mingled her thick dark blood with the dust…when they had torn open her shirtwaist, still damp with perspiration, they saw that her left breast was swinging loose like a flap, and there was no need to listen for the heart beneath. The mouth was wide open and ripped at the corners, as though she had choked a little in giving up the tremendous vitality she had stored so long.”

Dreams

Both of the sleeping and aspirational variety show up in haunting ways in The Great Gatsby.

Gatsby is plagued by both. First, the aspirational: “No—Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men.”

Knowing that Gatsby dies, this quote suggests that there are things far more frightening than death. In Gatsby’s case, he “paid a high price for living too long with a single dream.”

In fact, in his beginnings, the dream of his future sounds like a nightmare: “But his heart was in a constant, turbulent riot. The most grotesque and fantastic conceits haunted him in his bed at night. A universe of ineffable gaudiness spun itself out in his brain while the clock ticked on the wash-stand and the moon soaked with wet light his tangled clothes upon the floor. Each night he added to the pattern of his fancies until drowsiness closed down upon some vivid scene with an oblivious embrace. For a while these reveries provided an outlet for his imagination; they were a satisfactory hint of the unreality of reality, a promise that the rock of the world was founded securely on a fairy’s wing.”

At the end, Nick has this nightmare:

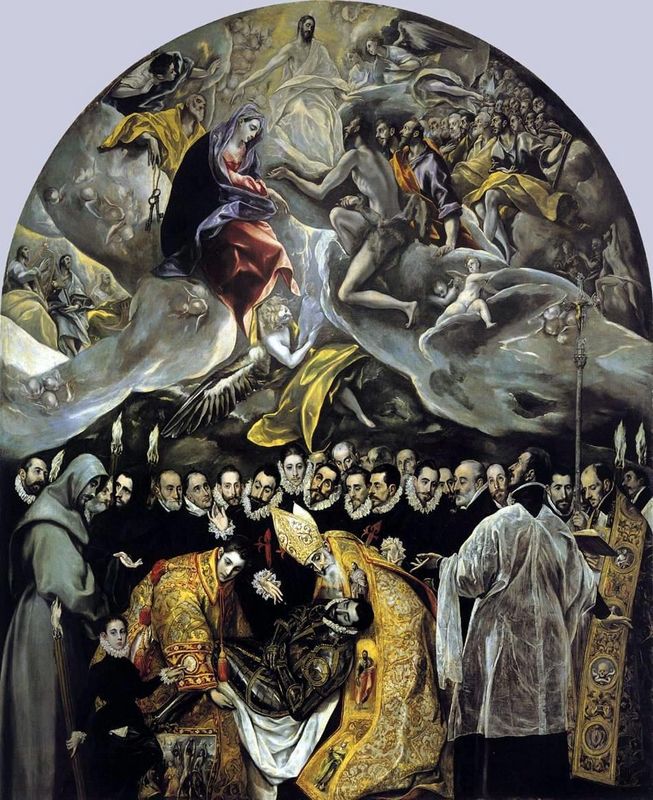

“West Egg, especially, still figures in my more fantastic dreams. I see it as a night scene by El Greco: a hundred houses, at once conventional and grotesque, crouching under a sullen, overhanging sky and a lustreless moon. In the foreground four solemn men in dress suits are walking along the sidewalk with a stretcher on which lies a drunken woman in a white evening dress. Her hand, which dangles over the side, sparkles cold with jewels. Gravely the men turn in at a house — the wrong house. But no one knows the woman’s name, and no one cares.”

So, Why?

I’ve spent a lot of time wondering why Fitzgerald established a haunting mood for The Great Gatsby. As of now, I have several hypotheses. First, the work has more to do with the atrocities of war than we ever give it credit for, and as such, can be viewed as a way to talk about war without talking war very directly. Second, the terror we all live with is too understated for what we feel. If you get real serious about it, life is scary. At any point, you can make a decision that will take you down a path of no return, so you might waste your own life that way. Or you could die in a car accident. This fragility is scary, but again, it requires a light hand to explore it without leading your readers into complete existential disarray. Thus, a story that is quite fantastic can work as an alternative medium. He’s also highlighting the terror of oppression (wealth disparity, people of color, and women) in a way that’s still relevant today.

What do you think? Why might Fitzgerald have utilized so much horror in this non-horror work?